A patent attorney digresses.

I recently read an article by Professor Margaret Boden on “Robot Needs”. While I agree with much of what Professor Boden says, I feel we can be more precise with our questions and understanding. The answer is more “maybe” than “no“.

Warning: this is only vaguely IP related.

Definitions & Embodiment

First, some definitions (patent attorneys love debating words). The terms “robot”, “AI” and “computer” are used interchangeably in the article. This is one of the problems of the piece, especially when discussing “needs”. If a “computer” is simply a processor, some memory and a few other bits, then yes, a “computer” does not have “needs” as commonly understood. However, it is more of an open question as to whether a computing system, containing hardware and software, could have those same “needs”.

AI

This brings us to “AI”. The meaning of this term has changed in the last few years, best seen perhaps in recent references to an “AI” rather than “AI” per se.

- In the latter half of the twentieth century, “AI” was mainly used in a theoretical sense to refer to non-organic intelligence. The ambiguity arises with the latter half of the term. “Intelligence” means many different things to many different people. Is playing chess or Go “intelligent”? Is picking up a cup “intelligent”? I think the closest we come to agreement is that it generally relates to higher cortical functions, especially those demonstrated by human beings.

- Since the “deep learning” revival broke into public consciousness (2015+?) “AI” has taken on a second meaning: an implementation of a multi-layer neural network architecture. You can download an “AI” from Github. “AI” here could be used interchangeably with “chatbot” or a control system for a driverless car. On the other hand, I don’t see many people referring to SQL or DBpedia as an “AI“.

- “AI” tends to be used to refer more to the software aspects of “intelligent” applications rather than a combined system of server and software. There is a whiff of Descartes: “AI” is the soul to the server “body“

Based on that understanding, do I believe an “AI” as exemplified by today’s latest neural network architecture on Github has “needs“? No. This is where I agree with Professor Boden. However, do I believe that a non-organic intelligence could ever have “needs“? I think the answer is: Yes.

Robots

This leads us to robots. A robot is more likely to be seen as having “needs” than “AI” or a “computer“. Why is this?

Robots have a presence in the physical world – they are “embodied“. They have power supplies, motors, cameras, little robotic arms, etc. (Although many forget that your normal rack servers share a fair few components.) They clearly act within the world. They make demands on this world, they need to meet certain requirements in order to operate. A simple one is power; no battery, no active robot. I think most people could understand that, in a very simple way, the robot “needs” power.

Let’s take the case where a robot is powered by a software control system. Now we have a “full house“: a “robot” includes a “computer” that executes an “AI“. But where does the “need” reside? Again, it feels wrong to locate it in the “computer” – my laptop doesn’t really “need” anything. Saying an “AI” “needs” something is like saying a soul “needs” food (regardless of whether you believe in souls). We then fall back on the “robot“. Why does the robot feel right? Because it is the most inclusive abstract entity that encompasses an independent agent that acts in the world.

Needs, Goals & Motivation

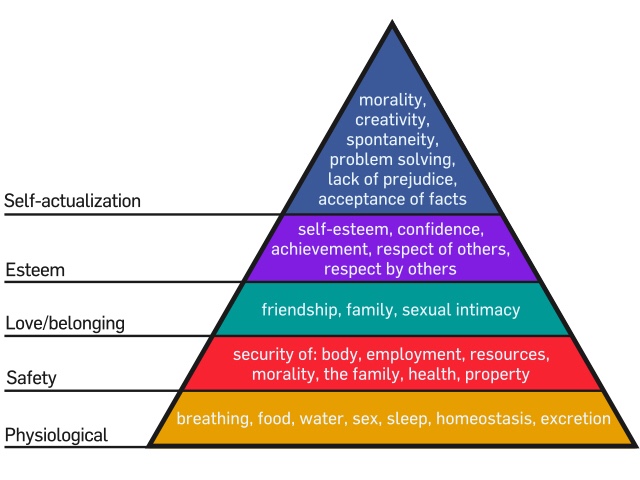

Before we take things further lets go on a detour to look at “needs” in more detail. In the article, “needs” are described together with “goals” and “motivation“. Maslow’s famous pyramid features. In this way, a lot is packaged into the term.

Maslow’s Pyramid – By Factoryjoe on WikiCommons

Maslow’s Pyramid – By Factoryjoe on WikiCommonsCan we have “needs” without “goals“? Possibly. A quick google shows several articles on “What Bacteria Need to Live” (clue: raw chicken and your kitchen). I think we can relatively safely say that bacteria “need” food and water and a benign environment. Do bacteria have “goals“? Most would say: No. “Goals“, especially as used to describe human behaviour, suggests the complex planning and goal-seeking machinery of the human brain (e.g. as a crude generalisation: the frontal lobes and corpus striatum amongst others). So we need to be careful mixing these – we have a term that may be applied to the lowest level of life, and a term than possibly only applies to the highest levels of life. While robots could relatively easily have “needs“, it would be more much difficult to construct one with “goals“. We would also stumble into “motivation” – have does a robot transform a “need” into a “goal” to pursue it?

Now, as human beings we instinctively know what “motivation” feels like. It is that feeling in the bladder that drives you off your chair to the toilet; it is the itchy uneasiness and dull empty abdominal ache that propels you to the crisp packet before lunch; it is the parched feeling in the throat and the awareness that your eyes are scanning for a chiller cabinet. It is harder to put it into words, or even to know where it starts or ends. Often we just do. Asked why we are doing what we do and the brain makes up a story. Sometimes there is a vague correlation between the two.

Now this is interesting. Let’s have a look at brains for more insight.

Brains

Nature is great. She has evolved at least the Earth’s most efficient data processing device (ignore that the “she” here also doesn’t really exist). Looking at how she has done this allows us to cheat a little when building robots.

A first thing to note is that nature is lazy and stupid (hurray!). She recycles, duplicates, always takes the easy option. This paradoxically means we have arrived at efficiency through inefficiency. Brains started out as chemical gradients, then rudimentary cellular architecture to control these gradients, then multi-cellular architectures, nervous passageways, spinal cords, brain stems, medullas, pons, mid-brains, limbic structures and cortex. Structures are built on top of structures and wired up in ways that would give an electrician a heart attack. Plus structures are living – they change and grow over time within an environment.

In the brain “needs“, at least those near the bottom of the Maslowian pyramid, map fairly nicely onto lower brain structures: the brain stem, medulla, pons, and mid-brain. The thalamus helps to bridge the gap between body and cortex. The cortex then stores representations of these “needs“, and maps them to and from sensory representations. Another crude and incorrect generalisation, but those lower structures are often called the “lizard brain“, as those bits of neural hardware are shared with our reptilian cousins. The raw feeling of “needs” such as hunger, thirst, sexual desire, escape and attack is possibly similar across many animals. What does differ is the behaviour and representations triggered in response to those needs, as well as the top down triggering (e.g. what makes a human being fear abstract nouns).

To quote from this article on cortical evolution:

Comparative studies of brain structure and development have revealed a general bauplan that describes the fundamental large-scale architecture of the vertebrate brain and provides insight into its basic functional organization. The telencephalon not only integrates and stores multimodal information but is also the higher center of action selection and motor control (basal ganglia). The hypothalamus is a conserved area controlling homeostasis and behaviors essential for survival, such as feeding and reproduction. Furthermore, in all vertebrates, behavioral states are controlled by common brainstem neuromodulatory circuits, such as the serotoneric system. Finally, vertebrates harbor a diverse set of sense organs, and their brains share pathways for processing incoming sensory inputs. For example, in all vertebrates, visual information from the retina is relayed and processed to the pallium through the tectum and the thalamus, whereas olfactory input from the nose first reaches the olfactory bulb (OB) and then the pallium.

“Needs” near the middle or even the top of Maslow’s pyramid are generally mammalian needs. These include love, companionship, acceptance and social standing. Consensus is forming that nature hijacked parental bonds, especially those that arise from and encourage breast feeding, to build societies. An interesting question is does this require the increase in cortical complexity that is seen in mammals? These “needs” mainly arise from the structures that surround the thalamus and basal ganglia, as well as mediators such as oxytocin. So that pyramid does actually have a vague neural correlate; we build our social lives on top of a background of other more essential drives.

The top of Maslow’s pyramid is contentious. What the hell is self-actualisation? Being the best you you can be? What does that mean? The realisation of talents and potentialities? What if my talent is organising people to commit genocide? Rants aside, Wikipedia gives us something like:

Expressing one’s creativity, quest for spiritual enlightenment, pursuit of knowledge, and the desire to give to and/or positively transform society are examples of self-actualization.

What these seem to be are human qualities that are generally not shared with other animals. Creativity, spirituality, knowledge and morality are all enabled by the more developed cortical areas found in human beings, as coordinated by the frontal lobes, where these cortical areas feed back to both the mammalian and lower brain structures.

A person may thus be likened to a song. The beat and bass provided by the lower brain structures, lead guitar and vocals by the mammalian structures, and the song itself (in terms of how these are combined in time) by the enlarged cortex.

Back to Needs

We can now understand some of the problems that arise when Professor Boden refers to “needs“. Human “needs” arise at a variety of levels, where higher levels are interconnected with and feed back to lower levels. Hence, you can take about “needs” such as hunger relatively independently of social needs, but social needs only arise in systems that experience hunger. There is thus a question of whether we can talk about social needs independent of lower needs.

We can also see how the answer to the question: “can robots ever have needs?” ignores this hierarchy. It is easier to see how a robot could experience a “need” equivalent to hunger than it is to see it experience a “need” equivalent to acceptance within a social group. It is extremely difficult to see how we could have a “self-actualised” robot.

Environment

Before we look at whether robots care we also need to introduce “the environment“. Not even human beings have “needs” in isolation. Indeed, a “need” implies something is missing, if an environment fulfils the requirement of a need, is it still a “need“?

Additionally, behaviour that is not suited to an environment would fall outside most lay definitions of “intelligence“. “Intelligence” is thus to a certain extent a modelling of the world that enables environmental adaptation.

The environment comes into play in two areas: 1) human “needs” have evolved within a particular “environment“; and 2) a “need” is often expressed as behaviour that obtains a requirement from the “environment” that is not immediately present.

Food, water, a reasonable temperature range (10 to 40 degrees Celsius), and an absence of harmful substances are fairly fundamental for most life; but these are actually a mirror image of the physical reality in which life on Earth evolved. If our planet had an ambient temperature of 50 to 100 degrees Celsius, would we require warmth? Can non-hydrogen-based life exist without water? Could you feed off cosmic rays?

These are not ancillary points. If we do create complex information processing devices that act in the world, where behaviour is statistical and environment-dependent, would their low-level needs over with ours? At presence it appears that a source of electrical power is a fairly fundamental “robot” or “AI” need. If that electrical power is generated from urine , do we have a “need” for power or for urine? If urine is correlated with over-indulging on cider at a festival, does the “AI” have a “need” for inebriated festival goers?

The sensory environment of robots also differs from human beings. Animals share evolutionary pathways for sensory apparatus. We have similar neuronal structure to process smell, sight, sound, motor-feedback, touch and visceral sensations, at least at lower levels of processing complexity. In comparison, robots often have simple ultrasonic transceivers, infra-red signalling, cameras and microphones. Raw data is processed using a stack of libraries and drivers. What would evolution in this computing “environment” look like? Can robots evolve in this environment?

Do robots have “needs“?

So back to “robots“. It is easier to think about “robots” than “AI“, as they are embodied in a way that provides an implicit reference to the environment. “AI” in this sense may be used much as we use “brain” and “mind” (it being difficult with deep learning to separate software structure from function).

Do robots have “needs“? Possibly. Could robots have “needs“? Yes, fairly plausibly.

Given a device with a range of sensory apparatus, a range of actuators such as motors, and modern reinforcement learning algorithms (see here and here) you could build a fairly autonomous self-learning system.

The main problem would not be “needs” but “goals“. All the reinforcement learning algorithms I am aware of require an explicit representation of “good“, normally in the form of a “score“. What is missing is a mapping between the environment and the inner state of the “AI“. This is similar to the old delineation between supervised and unsupervised learning. It doesn’t help that roboticists skilled at representing physical hardware states tend to be mechanical engineers, whereas AI researchers tend to be software engineers. It requires a mirroring of the current approach, so that we can remove scores altogether (this is an aim of “inverse reinforcement learning“). While this appears to be a lacuna in most major research efforts, it does not appear insurmountable. I think the right way to go is for more AI researchers to build physical robots. Physical robots are hard.

Do robots care?

Do most “robots” as currently constructed “care“? I’d agree with Professor Boden and say: No.

“Care” suggests a level of social processing that the majority of robot and AI implementations currently lack. Being the self-regarding species that we are, most “social” robots as currently discussed refer to robots that are designed to interact with human beings. Expecting this to naturally result in some form of social awareness or behaviour is nonsensical: it is similar to asking why flies don’t care about dogs. One reason human beings are successful at being social is we have a fairly sophisticated model of human beings to go on: ourselves. This model isn’t exact (or even accurate), and is largely implemented below our conscious awareness. But it is one up from the robots.

A better question is possibly: do ants care? I don’t know the answer. One one hand: No, it is difficult to locate compassion or sympathy within an ant. On the other hand: Yes, they have complex societies where different ants take on different roles, and they often act in a way that benefits those societies, even to the detriment of themselves. Similarly, it is easier to design a swarm of social robots that could be argued to “care” about each other than it is to design a robot that “cares” about a human being.

Also, I would hazard to guess that a caring robot would first need to have some form of autonomy; it would need to “care” about itself first. An ant that cannot acquire its own food and water is not an ant that can help in the colony.

Could future “robots” “care“? Yes – I’d argue that it is not impossible. It would likely require a complex representation of human social needs but maybe not the complete range of higher human capabilities. There would always be the question of: does the robot *truly* care? But then this question can be raised of any human being. It is also a fairly pertinent question for psychopaths.

Getting Practical

Despite the hype, I agree with Professor Boden that we are a long way away from any “robot” and “AI” operating in a way that is seen as nearing human. Much of the recent deep learning success involve models that appear cortical, we seem to have ignored the mammalian areas and the lower brain structures. In effect, our rationality is trying to build perfectly rational machines. But because they skip the lower levels that tie things together, and ignore the submerged subconscious processes that mainly drive us, they fall short. If “needs” are seen as an expression of these lower structures and processes, then Professor Boden is right that we are not producing “robots” with “needs“.

As explained above though, I don’t think creating robots with “needs” is impossible. There may even be some research projects where this is the case. We do face the problem that so far we are coming at things backwards, from the top-down instead of the bottom-up. Using neural network architectures to generate representations of low-level internal states is a first step. This may be battery levels, voltages, currents, processor cycles, memory usage, and other sensor signals. We may need to evolve structural frameworks in simulated space and then build upon these. The results will only work if they are messy.